Göbekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe Turkish: [ɡøbe̞kli te̞pɛ] ("Potbelly Hill") is a

Neolithic hilltop sanctuary erected at the top of a mountain ridge in

the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, some 15 kilometers (9 mi)

northeast of the town of Şanlıurfa (formerly Urfa / Edessa). It is the

oldest known human-made religious structure. The site was most

likely erected in the 10th millennium BCE and has been under excavation

since 1994 by German and Turkish archaeologists. Together with Nevalı

Çori, it has revolutionized understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic.

Göbekli

Tepe is located in southeastern Turkey. It was first noted in a survey

conducted by Istanbul University and the University of Chicago in 1964,

which recognized that the hill could not entirely be a natural feature

and postulated that a Byzantine cemetery lay beneath. The survey noted a

large number of flints and the presence of limestone slabs thought to

be Byzantine grave markers. This work was first mentioned in print in

Peter Benedict's article "Survey Work in Southeastern Anatolia" (1980).

In 1994, archaeologist Klaus Schmidt of the German Archaeological

Institute of Istanbul noted Benedict's article and visited the site,

recognizing that it was in fact a much older Neolithic site. Since

1995 excavations have been conducted by the German Archaeological

Institute of Istanbul and the Şanlıurfa Museum, under the direction of

Schmidt (University of Heidelberg 1995--2000, German Archaeological

Institute 2001--present). The hill had been under agricultural

cultivation before being excavated. Generations of local inhabitants had

frequently moved rocks and placed them in clearance piles and much

archaeological evidence may have been destroyed in the process. Scholars

from the Hochschule Karlsruhe began documenting the architectural

remains and soon discovered T-shaped pillars facing south-east. Some of

these pillars had apparently undergone attempts at destruction, probably

by farmers who mistook them for ordinary large rocks.

Göbekli Tepe on National Geography

Göbekli Tepe

Joe Rogan and Duncan Trussell talk about ancient cataclysms and the Göbekli Tepe ruins. Audio from The Joe Rogan Experience Podcast. Animated by Paul Klawiter- www.KlawiterStudios.com

Gobekli Tepe Stone Circles

Disclose.tv - Ancient Aliens: Unexplained Structures pt 1/3

Gobekli Tepe (Turkish for "Hill with a potbelly") is a hilltop sanctuary

erected on the highest point of an elongated mountain ridge some 15 km

northeast of the town of Sanliurfa(formerly Urfa / Edessa) in

southeastern Turkey. The site, currently undergoing excavation by German

and Turkish archaeologists, was erected by hunter-gatherers in the 10th

millennium BC (ca. 11,500 years ago), before the advent of sedentism.

Mysteriously, the entire complex of stones, pillars and carvings was

then deliberately buried in 8000 BC. Together with Nevalõ Cori, it has

revolutionized understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic.

Gobekli Tepe is located in southeastern Turkey. It had already been

noted in an American survey in 1964, which recognized that the hill

could not entirely be a natural feature, but assumed that a Byzantine

cemetery lay beneath. Since 1994 excavations have been conducted by the

German Archaeological Institute (Istanbul branch) and Sanliurfa Museum,

under the direction of the German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt

(1995Ð2000: University of Heidelberg; since 2001: German Archaeological

Institute). Schmidt says that the stone fragments on the surface made

him aware immediately that the site was prehistoric. Before then, the

hill had been under agricultural cultivation; generations of local

inhabitants had frequently moved rocks and placed them in clearance

piles; much archaeological evidence may have been destroyed in the

process. Scholars from the Hochschule Karlsruhe began documenting the

architectural remains. They soon discovered T-shaped pillars, some of

which had apparently undergone attempts at smashing.

The Complex

Gobekli Tepe is the oldest human-made place of worship yet discovered.

Until excavations began, a complex on this scale was not thought

possible for a community so ancient. The massive sequence of

stratification layers suggests several millennia of activity, perhaps

reaching back to the Mesolithic. The oldest occupation layer (stratum

III) contains monolithic pillars linked by coarsely built walls to form

circular or oval structures. So far, four such buildings, with diameters

between 10 and 30m have been uncovered. Geophysical surveys indicate

the existence of 16 additional structures.

Stratum II, dated to Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) (7500-6000 BC), has

revealed several adjacent rectangular rooms with floors of polished

lime, reminiscent of Roman terrazzo floors. The most recent layer

consists of sediment deposited as the result of agricultural activity.

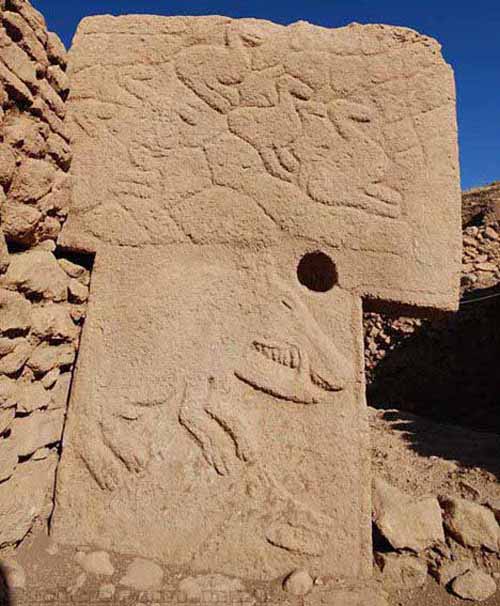

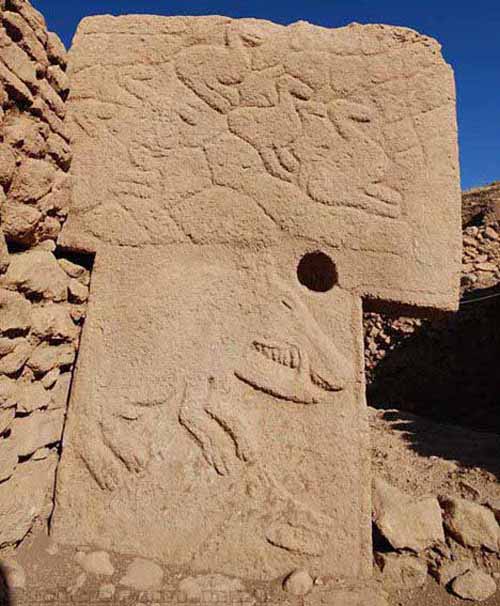

The monoliths are decorated with carved reliefs of animals and of

abstract pictograms. The pictograms cannot be classed as writing, but

may represent commonly understood sacred symbols, as known from

Neolithic cave paintings elsewhere. The carefully carved figurative

reliefs depict lions, bulls, boars, foxes, gazelles, asses, snakes and

other reptiles, insects, arachnids, and birds, particularly vultures and

water fowl. At the time the shrine was constructed the surrounding

country was much lusher and capable of sustaining this variety of

wildlife, before millennia of settlement and cultivation resulted in the

nearÐDust Bowl conditions prevailing today.

Vultures also feature in the iconography of the Neolithic sites of

‚atalhoyuk and Jericho; it is believed that in the early Neolithic

culture of Anatolia and the Near East the deceased were deliberately

exposed in order to be excarnated by vultures and other birds of prey.

(The head of the deceased was sometimes removed and preserved - possibly

a sign of ancestor worship.) This, then, would represent an early form

of sky burial.

Few humanoid forms have surfaced at Gobekli Tepe but include a relief of

a naked woman, posed frontally in a crouched position, that Schmidt

likens to the Venus accueillante figures found in Neolithic north

Africa; and of at least one decapitated corpse surrounded by vultures.

Some of the pillars, namely the T-shaped ones, have carved arms, which

may indicate that they represent stylized humans (or anthropomorphic

gods). Another example is decorated with human hands in what could be

interpreted as a prayer gesture, with a simple stole or surplice

engraved above; this may be intended to represent a temple priest.

Architecture

The houses or temples are round megalithic buildings. The walls are made

of unworked dry stone and include numerous T-shaped monolithic pillars

of limestone that are up to 3 m high. Another, bigger pair of pillars is

placed in the centre of the structures. There is evidence that the

structures were roofed; the central pair of pillars may have supported

the roof. The floors are made of terrazzo (burnt lime), and there is a

low bench running along the whole of the exterior wall.

The reliefs on the pillars include foxes, lions, cattle, wild boars,

wild asses, herons, ducks, scorpions, ants, spiders, many snakes, and a

very few anthropomorphic figures. Some of the reliefs have been

deliberately erased, maybe in preparation for new designs. There are

freestanding sculptures as well that may represent wild boars or foxes.

As they are heavily encrusted with lime, it is sometimes difficult to

tell. Comparable statues have been discovered at Nevali Cori and Nahal

Hemar.

The quarries for the statues are located on the plateau itself; some

unfinished pillars have been found there in situ. The biggest unfinished

pillar is still 6.9 m long; a length of 9m has been reconstructed. This

is much larger than any of the finished pillars found so far. The stone

was quarried with stone picks. Bowl-like depressions in the limestone

rocks may already have served as mortars or fire-starting bowls in the

epipalaeolithic. There are some phalloi and geometric patterns cut into

the rock as well; their dating is uncertain.

While the structures are primarily temples, more recently smaller

domestic buildings have been uncovered. Despite this, it is clear that

the primary use of the site was cultic and not domestic. Schmidt

believes this "cathedral on a hill" was a pilgrimage destination

attracting worshipers up to a hundred miles distant.

Butchered bones

found in large numbers from local game such as deer, gazelle, pigs, and

geese suggest that ritual feasting (and perhaps sacrifice) were

regularly practiced here.

The site was deliberately backfilled sometime after 8000 BC: the

buildings are covered with settlement refuse that must have been brought

from elsewhere. These deposits include flint tools like scrapers and

arrowheads and animal bones. The lithic inventory is characterized by

Byblos points and numerous Nemrik-points. There are Helwan-points and

Aswad-points as well.

Chronological Context

All statements about the site must be considered preliminary, as only

about 5% of the site's total area has been excavated as yet; floor

levels have been reached in only the second complex (complex B), which

also contained a terrazzo-like floor. Schmidt believes that the dig

could well continue for another fifty years. So far excavations have

revealed very little evidence for residential use. Through the

radiocarbon method, the end of stratum III can be fixed at circa 9,000

BC (see above); its beginnings are estimated to 11,000 BC or earlier.

Stratum II dates to about 8,000 BC.

Archaeologist Ofer Ben-Yosef of Harvard has said he would not be

surprised if evidence surfaces proving slave labor was involved which

would also represent something of a first, since hunting-gathering

communities are traditionally thought to have been egalitarian and to

predate slavery. At any rate, it is generally believed that an elite

class of religious leaders supervised the work and later controlled

whatever ceremonies took place here. If so, this would be the oldest

known evidence for a priestly caste - much earlier than such social

distinctions developed elsewhere in the Near East.

Around the beginning of the 8th millennium BC "Potbelly Hill" lost its

importance. The advent of agriculture and animal husbandry brought new

realities to human life in the area, and the "stone-age zoo" (as Schmidt

calls it) depicted on the pillars apparently lost whatever significance

it had had for the region's older, foraging, communities. But the

complex was not simply abandoned and forgotten, to be gradually

destroyed by the elements. Instead, it was deliberately buried under 300

to 500 cubic metres of soil. Why this was done is unknown, but it

preserved the monuments for posterity.

Interpretation and Importance

Gobekli Tepe is regarded as an archaeological discovery of the greatest

importance, since it profoundly changes our understanding of a crucial

stage in the development of human societies. It seems that the erection

of monumental complexes was within the capacities of hunter-gatherers

and not only of sedentary farming communities as had been previously

assumed. In other words, as excavator Klaus Schmidt put it: "First came

the temple, then the city." This revolutionary hypothesis will have to

be supported or modified by future research.

Schmidt considers Gobekli Tepe a central location for a cult of the

dead. He suggests that the carved animals are there to protect the dead.

Though no tombs or graves have been found so far, Schmidt believes they

remain to be discovered beneath the sacred circles' floors. Schmidt

also interprets it in connection with the initial stages of an incipient

Neolithic. It is one of several neolithic sites in the vicinity of

Mount Karaca Dag, an area where geneticists suspect the origins of at

least some of our cultivated grains (see Einkorn). Such scholars suggest

that the Neolithic revolution, i.e., the beginnings of grain

cultivation, took place here. Schmidt and others believe that mobile

groups in the area were forced to cooperate with each other to protect

early concentrations of wild cereals from wild animals (herds of

gazelles and wild donkeys). This would have led to an early social

organization of various groups in the area of Gobekli Tepe. Thus,

according to Schmidt, the Neolithic did not begin at a small scale in

the form of individual instances of garden cultivation, but started

immediately as a large-scale social organisation ("a full-scale

revolution").

Not only its large dimensions, but the side-by-side existence of

multiple pillar shrines makes the location unique. There are no

comparable monumental complexes from its time. Nevali Cori, a well-known

Neolithic settlement also excavated by the German Archaeological

Institute, and submerged by the Ataturk Dam since 1992, is 500 years

later, its T-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its shrine was

located inside a village; the roughly contemporary architecture at

Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture; and

Catalhoyuk, perhaps the most famous of all Anatolian Neolithic villages,

is 2,000 years younger.

Schmidt has engaged in some speculation regarding the belief systems of

the groups that created Gobekli Tepe, based on comparisons with other

shrines and settlements. He assumes shamanic practices and suggests that

the T-shaped pillars may represent mythical creatures, perhaps

ancestors, whereas he sees a fully articulated belief in gods only

developing later in Mesopotamia, associated with extensive temples and

palaces.

This corresponds well with an ancient Sumerian belief that agriculture,

animal husbandry and weaving had been brought to mankind from the sacred

mountain Du-Ku, which was inhabited by Annuna-deities, very ancient

gods without individual names. Klaus Schmidt identifies this story as an

oriental primeval myth that preserves a partial memory of the

Neolithic. It is also apparent that the animal and other images give no

indication of organized violence, i.e., there are no depictions of

hunting raids or wounded animals, and the pillar carvings ignore game on

which the society mainly subsisted, like deer, in favor of formidable

creatures such as lions, snakes, spiders and scorpions.

At present, Gobekli Tepe raises more questions for archaeology and

prehistory than it answers. We do not know how a force large enough to

construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was

mobilized and paid or fed in the conditions of pre-Neolithic society. We

cannot "read" the pictograms, and do not know for certain what meaning

the animal reliefs had for visitors to the site; the variety of fauna

depicted, from lions and boars to birds and insects, makes any single

explanation problematic.

As there seems to be little or no evidence of habitation, and the

animals depicted on the stones are mainly predators - with the exception

of gazelles, wild asses, insects and fowl - the stones may have been

intended to stave off evils through some form of magic representation.

Alternatively, they may have served as totems. It is not known why more

and more walls were added to the interiors while the sanctuary was in

use, with the result that some of the engraved pillars were obscured

from view. Burial may or may not have occurred at the site. The reason

the complex was eventually buried remains unexplained. Until more

evidence is gathered, it is difficult to deduce anything certain about

the originating culture.

Gobekli Tepe

Gobekli Tepe Wikipedia

Gobekli Tepe Google Videos

In the News ...

'World's Oldest Temple' May Have Been Cosmopolitan Center Live Science - March 16, 2012

Ancient blades made of volcanic rock that were discovered at what may be

the world's oldest temple suggest that the site in Turkey was the hub

of a pilgrimage that attracted a cosmopolitan group of people some

11,000 years ago.

The researchers matched up about 130 of the blades, which would have

been used as tools, with their source volcanoes, finding people would

have come from far and wide to congregate at the ancient temple site,

Gobekli Tepe, in southern Turkey. The blades are made of obsidian, a

volcanic glass rich with silica, which forms when lava cools quickly. he

research was presented in February at the 7th International Conference

on the Chipped and Ground Stone Industries of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic

in Barcelona, Spain.

Only a tiny portion of Gobekli Tepe has been excavated so far, but what

has been unearthed has been hailed by archaeologists as astounding for

its great age and artistry.The site contains at least 20 stone rings,

one circle built inside another, with diameters ranging from 30 to 100

feet (10 to 30 meters). The researchers suspect people would fill in the

outer ring with debris before building a new circle within.

T-shaped limestone blocks line the circles, and at their center are two

massive pillars about 18 feet (5.5 m) tall. Statues and reliefs of

people and animals were carved on these blocks and pillars. "Some of the

stones the big pillars are bigger than Stonehenge," said Tristan

Carter, one of the obsidian researchers and a professor of anthropology

at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. (Research on the site has

been ongoing since 1994 and is led by Klaus Schmidt of the German

Archaeological Institute.)

Even more puzzling is what has not been found. The buildings contain no

hearths and the plant and animal remains there show no signs of

domestication. Also, so far there have been no buildings found that

archaeologists can confirm were used for everyday living.

Taken together, the research indicates the site was created by

hunter-gatherers, rather than farmers, who came from across a large area

to build and then visit the site for religious purposes. This research

is backed up by the style of some of the obsidian and stone tools which

suggest that people were coming from Iraq, Iran, the Middle Euphrates

and the eastern Mediterranean.

The discoveries made at Gobekli Tepe over the past two decades have led

to a great deal of debate. Ted Banning, a professor of anthropology at

the University of Toronto in Canada recently published a paper in the

journal Current Anthropology arguing that interpretations of the site

may be off. Banning suggests the stone-ring structures may have been

roofed and used as houses, albeit ones filled with art that may have

served as both a domestic space and religious area. He also suggests

that the people of Gobekli Tepe could have been growing crops, pointing

out that some of the stone tools would have been useful for harvesting

and that, at such an early point in history, it is difficult to tell the

difference between wild plants and animals and those that humans were

trying to domesticate.

Volcanic Evidence

To try to solve some of the mysteries surrounding the site, Carter's

team has used a combination of scientific tests to match up the chemical

composition of the artifacts to the volcanoes from which the obsidian

originally came. "The real strength of our work is this incredible

specificity; we can say exactly which mountain it comes from, and

sometimes even which flank of the volcano," Carter told LiveScience in

an interview.

At least three of the obsidian sources are located in central Turkey, in

a region called Cappadocia, which is located nearly 300 miles (500 km)

away from Gobekli Tepe. At least three other sources are from the

eastern part of the country, close to Lake Van, about 150 miles (250 km)

away from the site. Yet another source is located in northeast Turkey,

also about 300 miles (500 km).

Researchers say that what make these results special are not so much the

distances involved - 300 miles would be a trip from New York City to

Buffalo, N.Y., sans any domesticated horses - but rather the sheer

variety of obsidian sources used. "It's an aberration," Carter said. The

obsidian finds back up "the idea of many people from many different

areas coming to the site," he said.

More Mystery

He cautioned that just because some of the obsidian came from such

distant sources, that doesn't mean that people were actually traveling

directly from these regions to Gobekli Tepe. The obsidian may have been

acquired by way of trade, turned into a tool, and then brought to the

site.

To try to resolve this problem, the team is also looking at the way the

obsidian tools were made. For example, they found that obsidian

artifacts sourced to Cappadocia, in central Turkey, tend to be

stylistically similar to artifacts found to the south of Gobekli Tepe in

the Middle Euphrates region of Mesopotamia. Also some of the obsidian

artifacts sourced to eastern Turkey, the Lake Van region, have

similarities to those made in Iraq and Iran. Altogether, these finds

suggest that some of the obsidian made its way south and east (possibly

through trade) before it was turned into tools and brought to the site,

another clue as to where people were coming from.

Though more research is needed to make any conclusive statements, if the

team is right, then Gobekli Tepe was indeed something grand, a place of

pilgrimage more than 11,000 years old that attracted people from across

the region. "If Professor Schmidt is correct, this represents a very

cosmopolitan area, this is almost the nodal point of the Near East,"

Carter said. "In theory, you could have people with different languages,

very different cultures, coming together."

The obsidian samples were analyzed at facilities at the MusŽe du Louvre

in Paris and McMaster University. In addition to Carter and Schmidt, the

team includes Franois-Xavier Le Bourdonnec and GŽrard Poupeau of the

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.